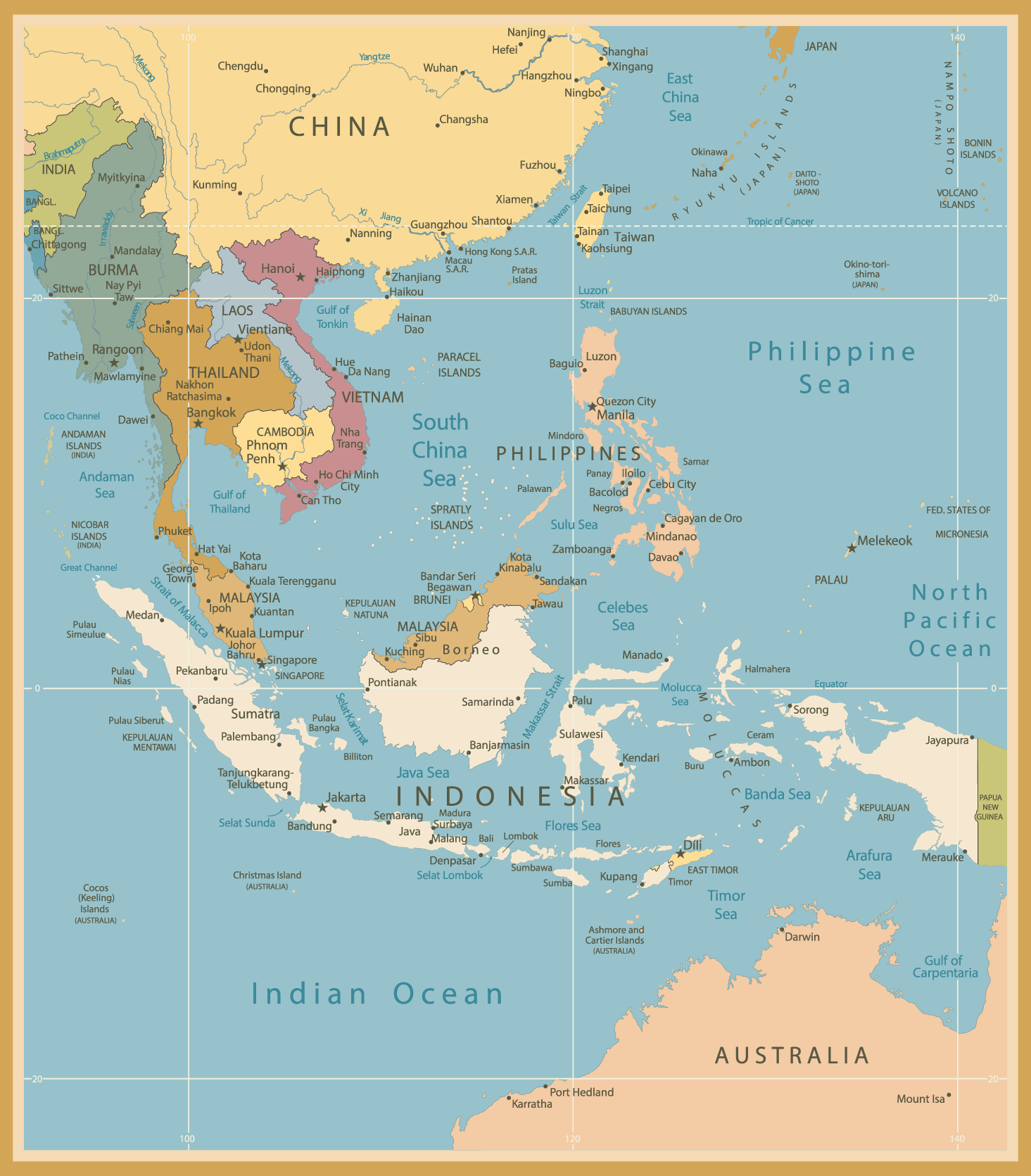

The food of Southeast Asia

Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore and beyond

ILLUSTRATION: SHUTTERSTOCK

ckbk co-founder Nadia Arumugam launches the first in our two-part series on the cuisines of Southeast Asia. Malaysia-born Nadia, who has lived in three countries and traveled widely in many more, couldn’t be a better guide to the region. She evokes the fragrant memories of her mother’s cooking and recalls the aromas, sounds and signature dishes of Malaysia’s capital, before taking us off to Singapore and Indonesia, then to South Africa’s Cape Malay cuisine. Nadia is also, of course, an expert guide to ckbk’s impressive collection of books from around the region.

I couldn’t have been more excited when Malaysian native Zaleha Olpin’s debut cookbook My Rendang Isn’t Crispy was made available on ckbk. The very title is a testament to Zaleha’s mission, her intent to share authentic Malaysian cooking with the world. The kind of homey cooking that mothers make for their families, with flavors refined over generations, the addictive cooking that Malaysians gorge themselves on perched on rickety plastic stools by roadside stalls first thing in the morning and last thing at night, the cooking that, as a Malaysian away from home, you dream about.

I too am Malaysian but I have lived much of my life away from the epicenter of the best food available on earth (perhaps I am biased, but I don’t think so). I grew up in London and have now spent over a decade in New York City. Despite the physical distance from my birth country, Malaysian food and the techniques integral to Malaysian cooking have been at the heart of how my mother cooked and, now, how I cook.

I am never without a jar of ground garlic, ginger and shallot purée in the fridge (the ratio of ingredients unconsciously absorbed from my mother). This pungent concoction, often with the addition of dried chili, is the basis of just about every Malaysian dish, whether a stir-fry, a curry, or as part of a marinade to coat fish or chicken before frying.

The rich mix of Malaysian cooking

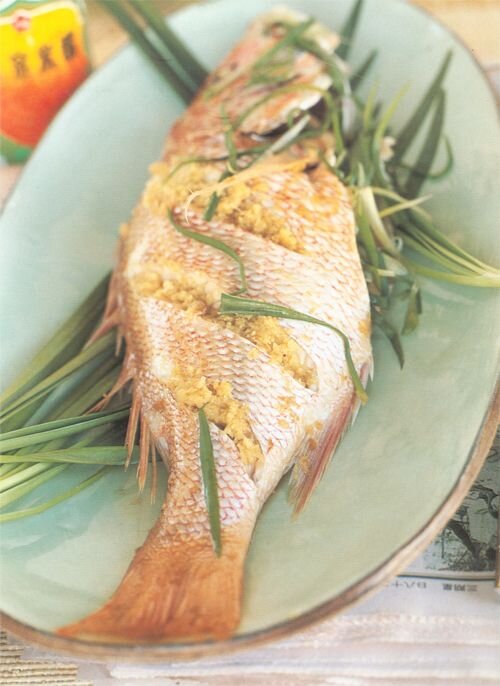

PHOTOGRAPH: BAB BOOKS FROM FLAVORS OF INDONESIA BY WILLIAM WONGSO

Malaysia’s unique multi-racial makeup is responsible for the glorious panoply of cuisines and sub-cuisines enjoyed by its food-obsessed citizens – a common trait shared by its population of Chinese, ethnic Malays and Indians of Tamil descent. Malaysian fare often characterized as ‘spicy.’ But it is so much more nuanced than that.

Certainly spices and fragrant aromatics such as cilantro, ginger, galangal, lemongrass, garlic and onion are used in abundance, but that doesn’t mean that every dish is infernally fiery (though Malaysians are partial to a fiery kick). There are plenty of stir-fry style dishes and stews that are soothing, rich and deeply flavorful but have no heat whatsoever. Served over rice, they can cure any number of ills.

Feasting, Malaysian-style: breakfast and lunch

PHOTOGRAPH: BAB BOOKS FROM FLAVORS OF INDONESIA BY WILLIAM WONGSO

Over the many long summer and winter breaks I spent in Kuala Lumpur while growing up, the days were punctuated with a multitude of feasts, small and large. Early in the morning, I would accompany my mother to the wet market. Live chickens awaiting slaughter, whole, glistening fish as fresh as can be, blue crabs struggling to escape their bindings, vast arrays of just-picked greens – the whole spectacle was a sensorial assault of the best kind.

Once we shopped, we would breakfast at a nearby open-air eatery. I would often opt for noodles, curry laska with its brick-red coconut milk and spice-infused broth, or a plate of hokkien mee – thick egg noodles interspersed with crackly, crispy bits of fried pork skin and Chinese greens, tossed in a distinctive sweet and savory soy-based sauce.

Prawn mee was a firm favorite, a dish for true seafood lovers, reeking of shrimpy essence, with an unctuous broth made from prawn shells and pork bones, enlivened with a chili kick, would be ladled over a combination of egg noodles and thin rice noodles. A handful of cooked prawns and a garnish of fried onions, hard-boiled egg and blanched greens would finish it off to perfection.

Not long after, hunger pangs would come calling. Street vendors sell some of the best edible treats in this part of the world. A cooling glass of sugar cane juice pressed in front you was a cooling treat. For something more substantial, we might have opted for the Chinese dessert tau fu fah. Slivers of freshly made, silky, soft tofu would be spooned out of a tall metal canister and a sweet syrup made from cane sugar or dark, rich palm sugar would be poured over. Just recalling slurping this confection, warm, at the side of a dusty road, brings a satisfying smile to my face.

The options for lunch were enough to boggle the mind, but we were quick to make a decision lest our favorite eateries would fill up, and a banana leaf meal was a top choice. In the South Indian tradition, diners are served steaming mounds of rice on plates made from banana leaves and servers come around offering the daily menu of curries, sambar and vegetable dishes – each so distinctive and satisfying.

Alternatively, we would head to a mamak stall. These Indian Muslim joints are famous for their fried noodles anointed with a chili and tomato ketchup sauce and the moreish, flaky, feather-light flatbread roti canai. We would begin the meal by dousing torn-off handfuls of roti canai in a coconut milk-based chicken curry gravy so delicious you could drink it straight, and end with a second round of bread which we would eat dipped in sugar!

Afternoon tea, sweet and savory

Afternoon tea was a repast never to be missed. Malay cakes, or kuih, are delightful to look at with their bright colors and different layers, and these sweet confections are irresistible.

There are a host of different kinds of kuih. Every Malaysian has their favorite but freshly grated coconut, palm sugar, coconut milk, tapioca and pandanus leaf form the mainstay of ingredients. My personal downfall is kuih dadar or kuih ketayap – pandan and coconut-flavored pancakes wrapped around a jammy grated coconut and palm sugar filling.

For good measure, we would balance these super-sweet cakes with something savory like curry puffs – melt-in-the mouth pastry crescents filled with a spiced potato and chicken filling. The hawker versions were delicious but my mother’s were the best.

She would make them during the weekend even when we were all grown-up and paused our lives to return home to be fed. Following our noses, we’d hover around the wok waiting for curry puffs to emerge golden, crispy and searingly hot. The five minutes necessary for the pastries to cool sufficiently so you wouldn’t lose the skin form the roof of your mouth was torture. From hand to mouth, they would be decimated in seconds.

Home cooking: it’s what memories are made of

But I digress. For dinner, my mother’s home cooking was the most alluring choice (that is, when we weren’t tempted by chili crab, butter prawns or the freshest steamed whole fish with ginger and scallions at a local seafood eatery). Her chicken curry, South Indian in style but entirely her own, infused with the heady scent of curry leaves from our garden, and plenty of coriander, was legendary.

She would prepare her signature curry powder blend with total patience and absolute attention to every detail. Whole spices including cinnamon, star anise, dried chili, cumin and fennel, would be freshly procured in large amounts. She would meticulously wash them, sift them for debris and put them out in the sun on large trays until they were bone-dry.

Next, they would be slow roasted in a low oven. When completely cool, the spices would be bagged up and taken to a local mill first thing in the morning. My mother would always tip the foreman handsomely so that the mill workers would clean the machinery well and grind her spices before they attended to any other job to avoid contaminating her concoction. I made my mother’s final batch of curry powder with her in Kuala Lumpur last spring, just months before she passed away from cancer. I keep my batch in the freezer to maintain its freshness, already anticipating with immeasurable sadness the last curry that I will make from it.

Malaysian home cooking – in your home

I invite anyone who might wish to authentically enjoy the diverse culinary treasures that Malaysian fare offers to delve deeply into Olpin’s wonderfully accessible book. No need to be by deterred long lists of impossible-to-find ingredients.

When the judges on MasterChef UK doled out their judgment that Zaleha Olpin’s rendang “was not crispy enough” (having mistaken it for another dish, or simply been misinformed) she was entirely right to be indignant.

Rendang is a traditional Malay, and indeed Indonesian, beef curry (although chicken can be used too). The meat is slowly braised in a coconut milk, lemongrass and spice-infused gravy until the liquid has reduced to a very thick consistency and the meat is a deep dark brown hue, almost too tender to believe and intensely flavorful. It should be anything but crispy.

Olpin herself is an expatriate who has lived all over the world, including Australia, Japan, South Korea, the Middle East and the UK. Judiciously reformulating recipes from her home country with a disciplined hand using locally available ingredients became her forte. While freshly grated coconut is easily available in Southeast Asia and features prominently in Malaysian cuisine, it is near impossible to find elsewhere (if you are lucky you will find it frozen). No worries. Olpin breezily substitutes desiccated coconut to great success.

More Southeast Asian flavors to savor

But don’t stop with Olpin, who mostly sticks to Malay and Mamak recipes. Approach her book as a springboard to further explore the variety of Malaysian cuisine through Robert Danhi’s Southeast Asian Flavors: Adventures in Cooking the Foods of Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia & Singapore.

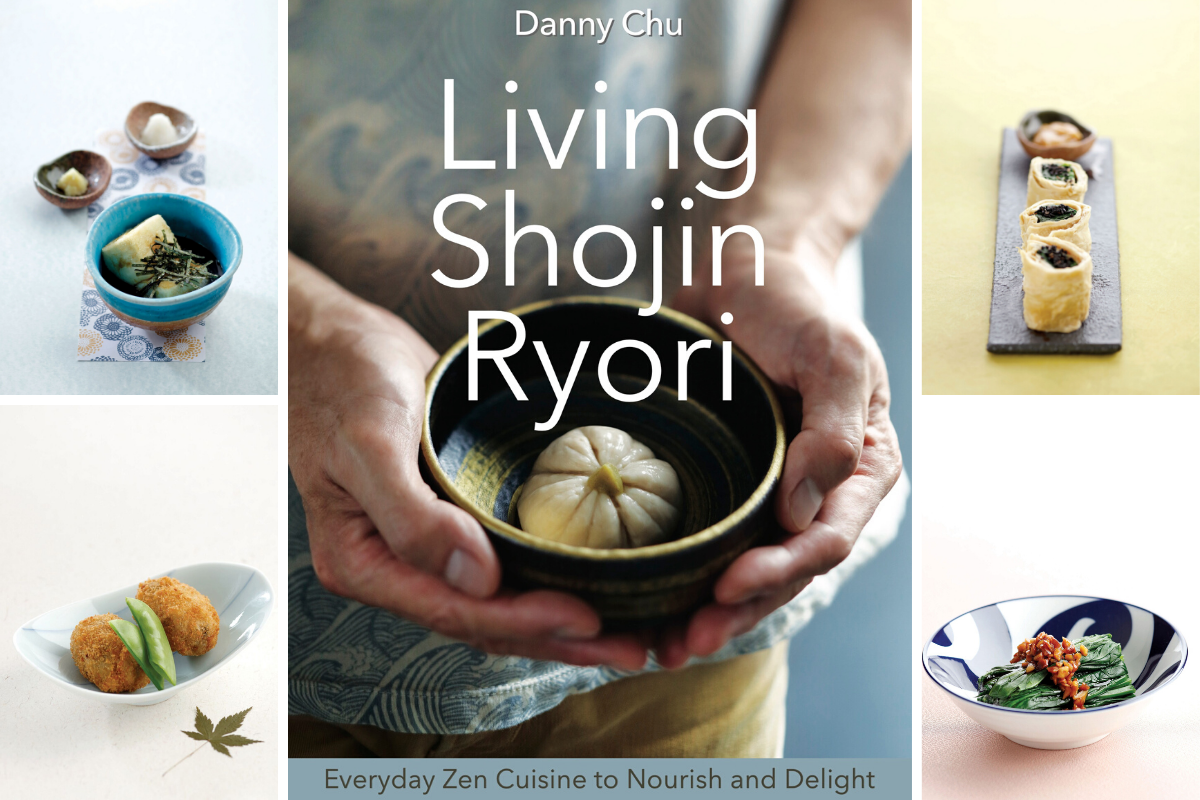

Once you’re immersed in cooking Malaysian fare, you might as well poke around the pantry of her neighbors and explore the menus on offer in Singapore and Indonesia. While you will see many of the same dishes, there are many distinctions waiting to be discovered. For instance, Malaysian satay tends to be sweeter than the Indonesian version and more intensely spiced. It also uses lemongrass prominently in the marinade, while the Indonesian satay does not.

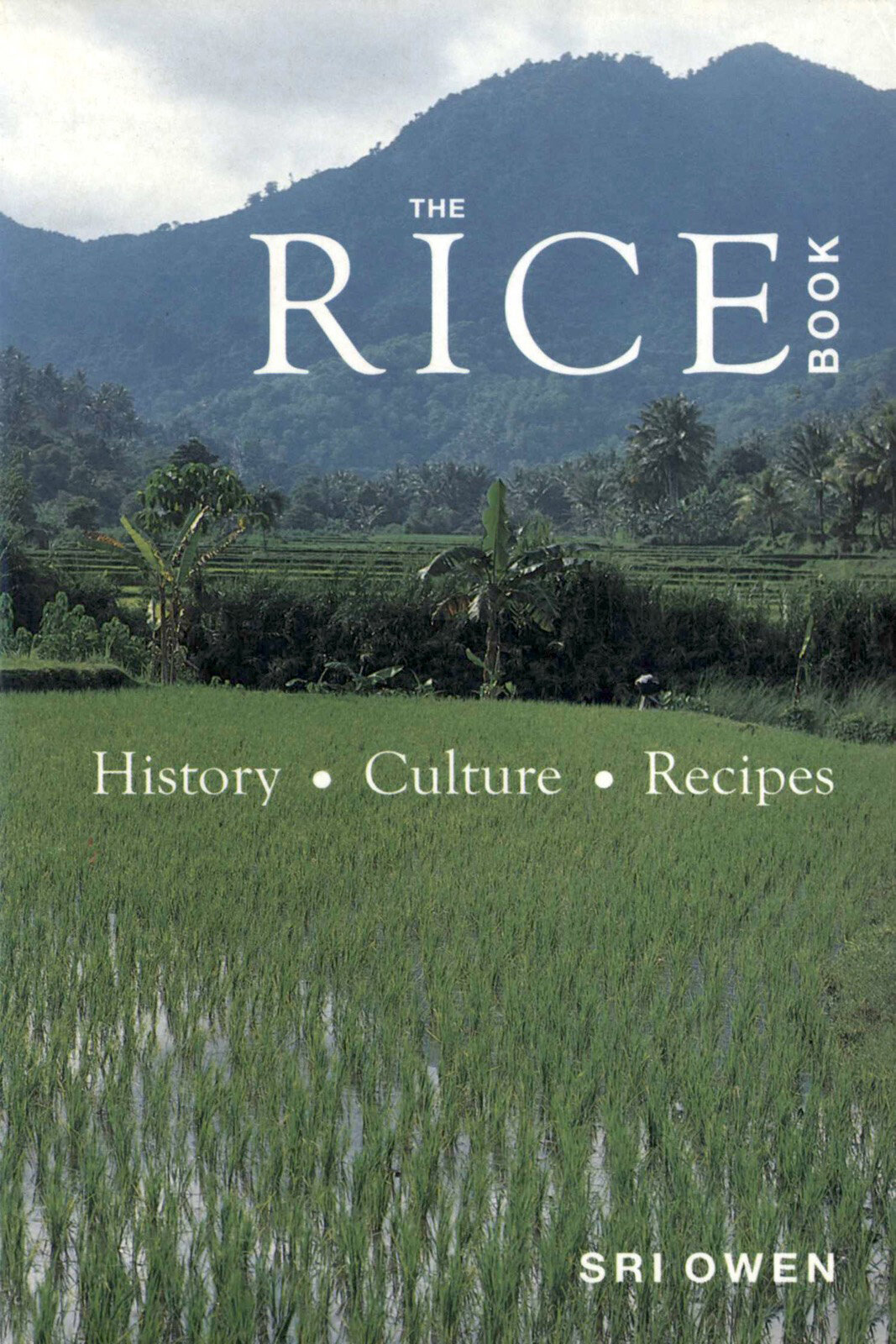

For Indonesian cuisine, you could find no better guide than award-winning cookbook author Sri Owen. I recall with vibrant detail the gloriously satisfying and tasty lunch that Sri prepared for me and my co-founder Matt Cockerill, at her beautiful home in London in 2016. We are lucky enough to have four of her books on ckbk: Indonesian Food and Cookery, Indonesian Regional Food and Cookery, The Rice Book, and New Wave Asian.”

Diaspora dishes: Cape Malay cooking

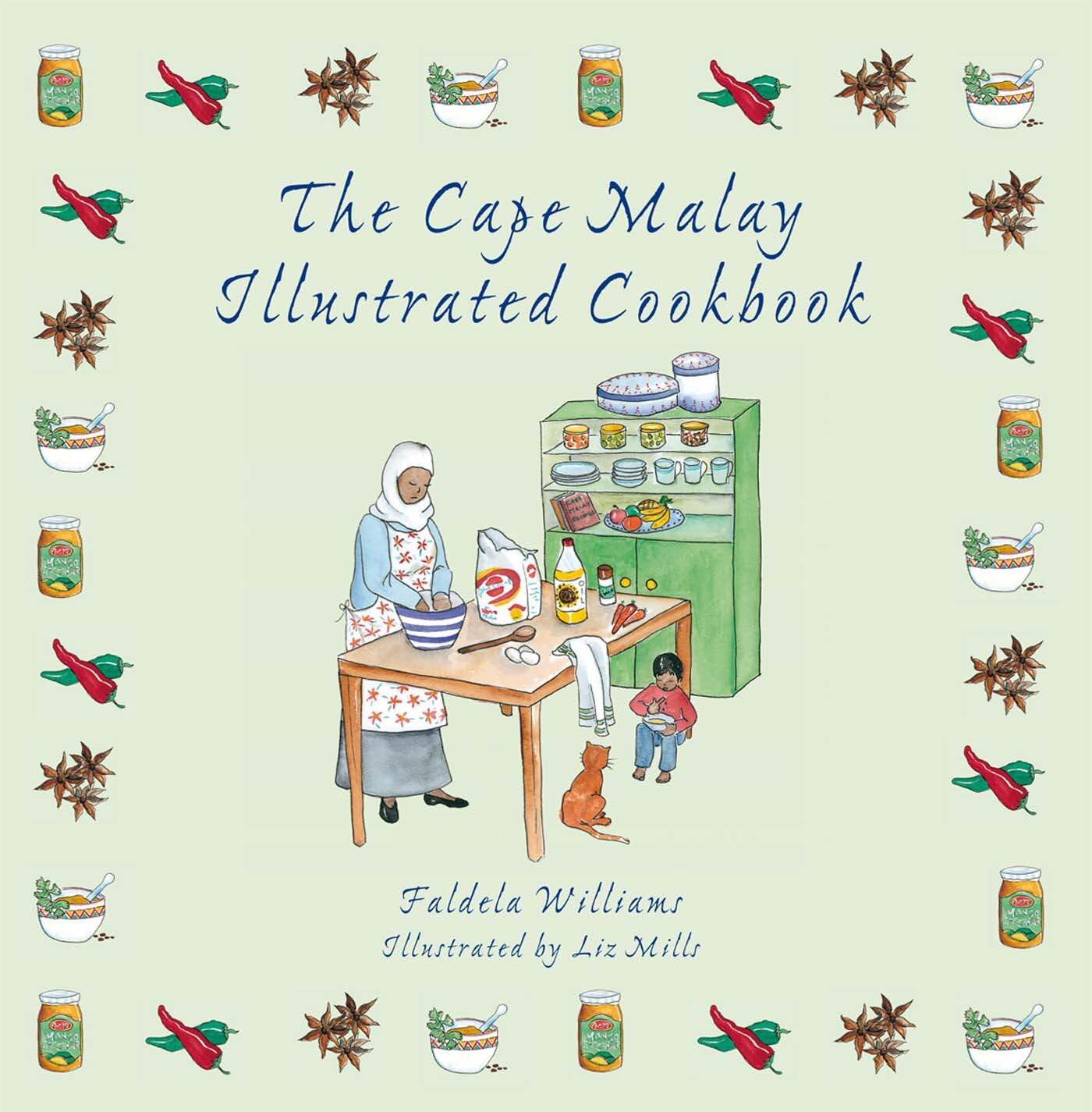

Many years ago while traveling through South Africa with my mother, we were fascinated to discover Cape Malay cooking. Richly flavored, comforting stews, curries, roasts and rice dishes featuring plenty of aromatic spices (think cinnamon, star anise, cardamom and coriander) countered with sweet dried fruit such as apricots and raisins – we were hooked.

This 300-year-old cuisine is native to the Western Cape of South Africa. It’s a unique fusion of Malaysian, Indonesian and East African culinary traditions that were introduced to the region by enslaved people brought by Dutch settlers in the 17th and 18th centuries. These people came from the Dutch East Indies, now known as Indonesia, and also from East Africa and Madagascar. Despite the diversity of their origins, the community, mostly Muslim, came to be known as the Cape Malay.

Perhaps my most favorite of the Cape Malay dishes I encountered is bobotie, a spiced meat casserole studded with raisins and topped with a savory custard. I was thrilled that when we toured Kenya on a safari expedition some time later, bobotie made a frequent appearance at dinner at the various safari camps we visited.

You’ll find an excellent recipe for it in The Cape Malay Illustrated Cookbook. This charming book is filled with intricate illustrations that provide a wonderful cultural context for the recipes within. It is worth spending time with and certainly cooking from.

I do hope that I have inspired you to explore the cache of great Southeast Asian cookbooks on ckbk, to go beyond the better known cuisines of Thailand and Vietnam, and to follow the diaspora as far afield as South Africa. Trust me, your taste buds will thank you.

Nadia Arumugam, co-founder of ckbk, was born in Kuala Lumpur and grew up in London, where she trained trained as a chef, and she now lives in New York City. She’s a cookbook author, award-winning food writer and editor, and a novice restaurant investor, as well as an indisputable lover of all things edible and culinary. Whether she’s perfecting her gourmet mac and cheese for her discriminating toddler or hosting multiple-course dinner parties, she (almost) always has something simmering on the stove.

Our Southeast Asia series continues with:

a culinary quiz from well-traveled food writer Naomi Duguid to test your mettle on Burmese cuisine

a roundup of recipe collections showcasing the best dishes from the Philippines, Burma, Cambodia and Laos

a few of our favorite Thai and Vietnamese recipes

Related Posts

French Food Quiz

Michelin-starred chef Daniel Galmiche lends his expertise to our French culinary quiz.