Behind the Cookbook: Science in the Kitchen and the Art of Eating Well

The latest book to be added to ckbk’s collection is Pellegrino Artusi’s masterwork, Science in the Kitchen and the Art of Eating Well.

The book is a foundational text on Italian cuisine, first published in 1891 (not long after Italian unification) and still of key relevance today. It is celebrated by contemporary Italian chefs such as Giorgio Locatelli (who has described it as “life-changing”) and by prominent writers including Bill Buford and Anna del Conte.

Roberta Muir is an Australian food writer, cookbook author and culinary educator with a special passion for the food of Italy and in this feature she puts Artusi’s work into context and highlights some of the familiar (and less familiar) Italian dishes which it has to offer.

by Roberta Muir

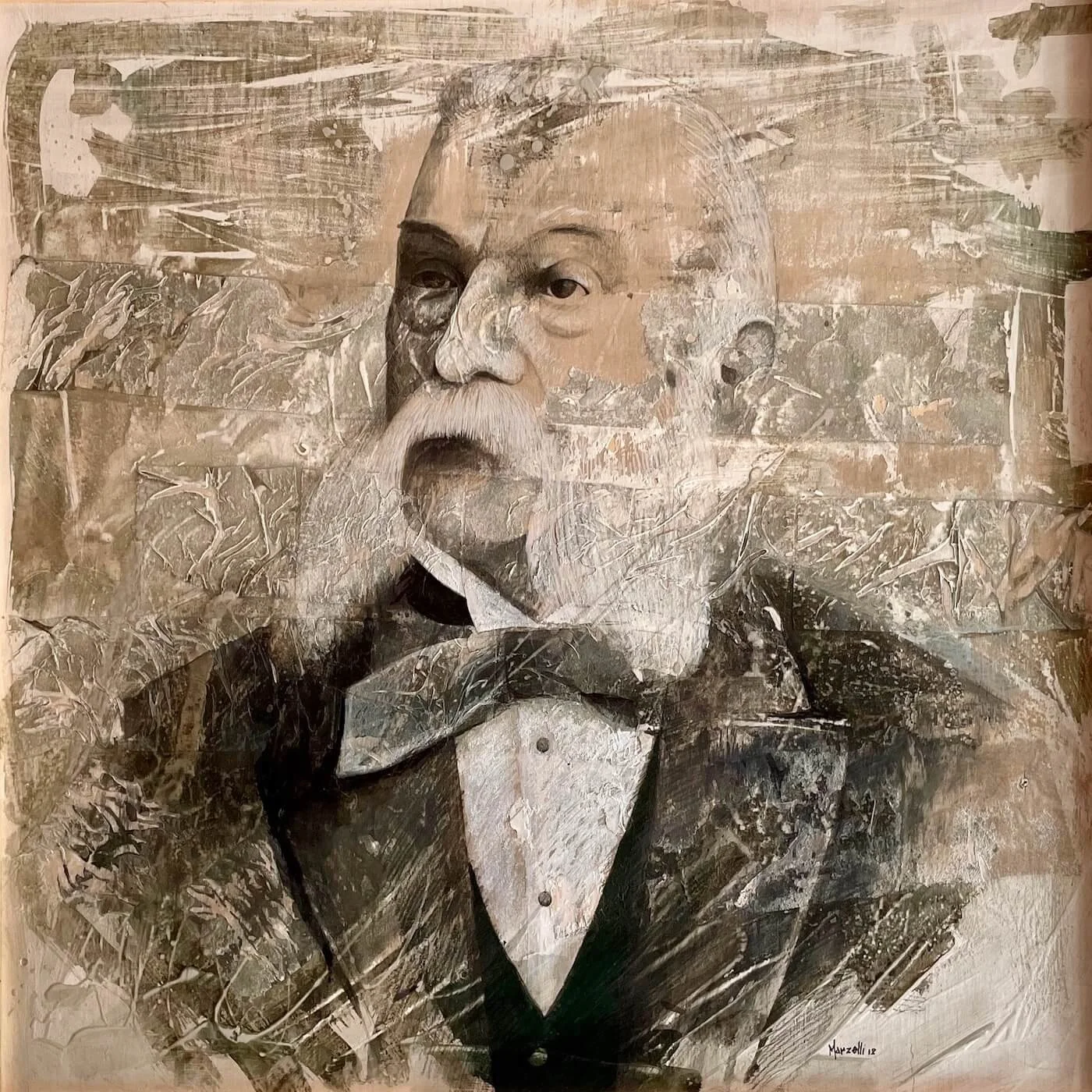

As part of a small group food and wine tour I recently led to northern Italy, I visited Casa Artusi, an institution dedicated to the work of 19th century Italian gastronome Pellegrino Artusi.

Artusi has been dubbed ‘the father of Italian home cookery’ for his book La Scienza in Cucina e l'Arte di Mangiare Bene (Science in the Kitchen and the Art of Eating Well). Published in 1891, just 30 years after Italy became a nation, it was the first comprehensive regional Italian manual for the home cook and Artusi is credited with being the first to define a truly national Italian cuisine.

Housed in a beautifully restored church in Artusi’s birthplace of Forlimpopoli in south-eastern Emilia-Romagna, Casa Artusi is a living museum of Artusi’s passions and work, including a library and research facility, cooking school and restaurant/function space.

Casa Artusi

Dying without an heir, Artusi left most of his wealth to the hometown he’d departed 60 years earlier, specifying that part of it be used for the creation of a public library.

Today the library in Casa Artusi houses many editions of La Scienza in Cucina in multiple languages as well as books about Artusi and his personal library and archive, including the Papal decrees that acted as passports for his travels around the Italian peninsula. There’s also a collection of letters to Artusi, many from home cooks who contributed recipes to his editions or wrote seeking clarification and advice.

Artusi’s papal passport

Artusi came from a successful merchant family and was well educated before taking over the family business. In 1851, when he was in his early 30s, his family was held hostage and robbed by a notorious outlaw and his sister Gertrude was raped, an ordeal from which she never recovered. No longer feeling safe in Forlimpopoli, the Artusi family moved to Florence where their business interests flourished.

By 1865, just a few years after Italian unification, having spent the past decade travelling the length and breadth of the Italian peninsula as a silk merchant, Artusi was wealthy enough to devote all his time to his two great passions: cooking and literature. He never married and, after his parents’ deaths until his at the age of 90, lived alone in his home on the then-private Piazza d'Azeglio in central Florence. His only companions were a butler and his cook, Mariette Sabatini.

Marietta was more than Artusi’s loyal servant, he credited her with being his teacher and collaborator and they shared many hours in the kitchen together. In the introduction to her panettone recipe. He says: “My Marietta is a good cook, and such a good-hearted, honest woman that she deserves to have this cake named after her, especially since she taught me how to make it.” At Casa Artusi, La Associazione delle Mariette is a team of local volunteers who teach cooking school guests to make Piadina Romagnola (the local flatbread) and egg-rich pastas.

La Scienza in Cucina e l'Arte di Mangiare Bene was first published in 1891 with 475 recipes that Artusi gathered, tested and refined (with Mariette’s assistance) over many years of travels. Artusi self-published after his manuscript was rejected by publishers in Florence and Milan, and sales were slow at first. By his death in 1911, however, he’d released 14 further editions, added another 315 recipes and sold 52,000 copies. The book has rarely been out of print in the 113 years since and has been translated into many languages including Spanish, French, Dutch, German, English, Japanese, Portuguese and Polish.

Artusi’s revised editions were enriched with recipes and suggestions sent to him by home cooks from all over Italy, which he and Mariette tested and refined in their Florentine kitchen. So La Scienza in Cucina is more than the work of one very dedicated researcher, cook and writer, it’s a collection of recipes from home cooks throughout Italy; many of which are as relevant and delicious today as they were 100 years ago.

While recipes for stewed frog , thrush in aspic and sturgeon may not have the broad appeal they once did, saltimbocca alla Romana, vitello tonnato and osso buco still appear on many Italian restaurant menus. There’s even a recipe for garlic bread, which he calls by the Romagna name Cresentine.

Cookbooks of the time were mostly written by French (or French-trained) chefs for professional cooks preparing food for wealthy families, not for simple home cooks with humble means. Artusi loved the rigour of testing and retesting recipes until he was satisfied with the results and wrote in an easy-to-follow style with entertaining stories and anecdotes from his travels. His book was like a travelogue, introducing readers to the recipes and stories from distant regions of the newly unified country.

His pasta dishes range the length of the country from a classic Bolognese ragù to a Neapolitan tomato sauce and a Sicilian pasta with sardines.

Pasta making demonstration at Casa Artusi

Though well-travelled, his Northern Italian sensibilities occasionally show, as when he describes a Neapolitan pasta as containing a “hodgepodge of spices and flavors … [that] did not turn out at all badly” and “may appeal to those whose taste buds are not categorically in favor of simplicity.”

Soups range from Minestra di Krapfen (with yeasted fritters) from German-speaking South Tyrol, to Tuscan Minestra di Pangrattato (thickened with stale bread) , and more southern Zuppa di Fagioli with a politely euphemistic warning about the potential side effects of eating beans.

He does however advise against serving food of one region to diners in another when he thinks it will not suit regional tastes, cautioning that the two-coloured Minestra di due Colori beloved of Tuscan ladies, will not be to the taste of those in his home region of Romagna where “softness to the bite is not to the locals’ taste.”

He was both witty and humble in his writing, a fan of basic dishes prepared simply with good quality, local ingredients. In a recipe for cheese fondue from Piedmont, he decries “gluttons who, like wolves, cannot distinguish, say a marzipan cake from a bowl of thistles.” And elsewhere says: “I should not like my interest in gastronomy to give me the reputation of being a gourmand or glutton.”

Rather than reporting simply on recipes he’d eaten or had described to him, Artusi was an ardent observer in every kitchen he came across. In the recipe for Riso alla Cacciatora (hunter-style rice) he tells the story of watching the cook in a road-side inn prepare a spontaneous meal for his companion and himself from what she had on hand. He then goes on to explain how he would improve upon this tasty dish when preparing it in his own kitchen.

More than a mere chronicler of recipes, Artusi is an encouraging teacher, reminding his readers that he too is an amateur and that if he can achieve delicious results, so can they with a little practice. His reassurance in the introduction to his strudel recipe is typical of his approach: “Do not be alarmed if this dessert looks like some ugly creature such as a giant leech or a shapeless snake after you cook it; you will like the way it tastes.”

He believed in adopting good taste wherever he found it and includes a recipe for ‘Salsa Verde che i Francesi Chiamano Sauce Ravigote’ (green sauce which the French call sauce ravigote) that he insists “deserves to become part of Italian cuisine because it goes well with poached fish, poached eggs, and so forth.”

His discussion on the regional dishes of Italy extend to one shared with him by members of Italy’s Jewish community for making couscous by hand, then cooking it in a meat broth as a first course.

His credits are often as interesting as his recipes, such as a pasta and egg soup, strichetti alla Bolognese, for which he thanks “a young, charming Bolognese woman known as la Rondinella, who was so good as to teach it to me.” While others such as anolini are from people he’d never met: “A woman from Parma, whom I have not the pleasure of meeting, wrote me from Milan, where she lives with her husband, as follows: ‘I take the liberty of sending you a recipe for a dish which in Parma, beloved city of my birth, is a tradition at family holiday gatherings. Indeed I do not believe there is a single household where the traditional ‘Anolini’ are not made at Christmas and Easter time.’ I declare myself indebted to this woman, because, having put her soup to the test, the result delighted not only myself but all my guests.”

In the introduction to Roman-style gnocchi made with semolina he says: “I hope [these gnocchi] will please you as much as they have delighted those for whom I have prepared them. Should that happen, toast to my health if I am still alive or say a requiescat in my name, if I have gone on to feed the cabbages.” For this recipe, and all 792 others, I think we should all say a requiescat for Pellegrino Artusi — mangia bene e buona cucina!

Roberta Muir now runs small-group food and wine tours to her beloved Italy – find out more.

Top recipes from Science in the Kitchen and the Art of Eating Well

More ckbk features

The Lombardian Cookbook, The Sardinian Cookbook and Wild Weed Pie, three books from Roberta Muir together with top Australian chefs

Guiliano Hazan on his cookbook which documents growing up and learning to cook as the son of Italian-American culinary icon, Marcella Hazan

Valentina Harris tells the story behing her magnum opus which covers the diverse local cuisines of Italy