How cookbooks from the past inform the food of the present

THE VINTAGE BOOKSHELF

We continue our vintage cookbook strand with a post from food writer Gemma Croffie, who understands the value of cookbooks from bygone eras.

There are plenty of reasons to read books from other eras, she says: they’re a window onto the past, they’re full of advice that’s actually useful – and they can be downright funny, too. Read them, cook from them, and you’ll also discover the roots of many of today’s cooking trends, from nose-to-tail eating to reducing meat.

Here are some of Gemma’s top picks from ckbk’s collection of vintage cookbooks…

As a child, I loved thumbing through Mum’s cookbooks. She only had a handful but the lurid pictures from the green doorstop that was the Good Housekeeping Cookbook captivated me. I agreed with Alice B. Toklas, who wrote: “Cookbooks have always intrigued and seduced me. When I was still a dilettante in the kitchen they held my attention, even the dull ones, from cover to cover.” I was also intrigued and seduced by cookbooks and the possibilities inherent in them.

It was all far removed from my reality of living under the hot Ghanaian sun. This was the food of books I read by Enid Blyton, Charles Dickens and Jane Austen – cold-weather food of puddings and dumplings and summer picnics with lashings of ginger beer.

So a fascination with food was born, latent until I was in my early twenties, living in England and beginning to tentatively try new recipes and cuisines.

Ahead of their time: Patience Gray and Hannah Glasse

Every year it seems a growing number of culinary superstars bring out shiny new books with impossibly perfect food pictures. I implore you to look the other way – at least temporarily – and look to the past, and to unearth some truths from cookbooks of a bygone era.

Why look to the past? There are plenty of reasons. The ingredients called for in vintage cookbooks tend to brevity (no Ottolenghi-length lists), have easy-to-find ingredients, and are often full of unsolicited advice that’s actually useful. They’re a window into history, and are sometimes downright funny too.

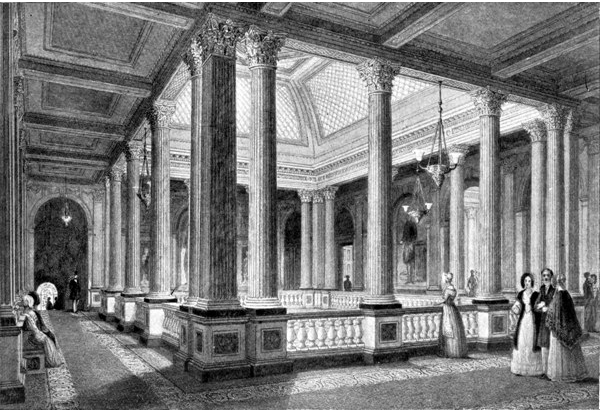

What’s more, chances are that what you think of as the ‘new’ in the food world has probably been written about before. Eat less meat? Patience Gray was advocating for it in the 1980s. Long before Spanish-American chef José Andrés (try his Grilled Bread with Chocolate recipe) founded World Central Kitchen, Alexis Soyer, chef de cuisine at London’s Reform Club, had set up a soup kitchen in Dublin during the Irish potato famine in the mid-19th century, and joined the troops (at his own expense) during the Crimean War in 1854; he even designed a portable stove to feed the hungry troops.

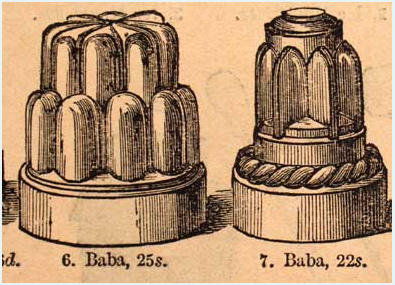

Making life easier and getting dinner on the table quickly? Hannah Glasse was advocating this (albeit for women only) in her The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy first published way back in 1747. Celebrity name-dropping and anecdotes? Pah, I would love to read the cookbook that can top Alice B Toklas’ mentions of Picasso and Gertrude Stein The Alice B. Toklas Cookbook.

Admittedly, some of the recipes in these books, like Rufus Estes’ Sheep’s Brains With Small Onions, will not be gracing my dining table anytime soon – although it is worth noting that the nose-to-tail movement, the push for seasonal eating and minimising food waste are old concepts.

Real recipes for real people

Alexis Soyer championed the idea that good cooking needn’t be the preserve of the wealthy. Soyer published A Shilling Cookery for the People in 1854, which Elizabeth David referred to the book as “a little mine of instructive information for a lone, unskilled and impecunious cook.” It was the first book with recipes adapted for working people, making use of simple utensils such as a frying pan. Some of it was written in the form of fictional letters from one cook to another.

The Reform Club in London, where Alexis Soyer was chef de cuisine.

Long before Delia Smith came along, Soyer was teaching people how to do basic things such as boil an egg. He also shamelessly plugs one of his previous books, suggesting that those who required sweet dishes purchase his book Modern Housewife, as “no doubt their pocket is equal to their taste.”

Soyer also understood the importance of pies. He would not have been surprised by the current proliferation of pie cookbooks on the market. In his opinion, in England pies were considered as one of the best companions in the voyage through life. Endearingly, he was certain that kitchen utensils given as wedding presents would be the greatest promoter of peace and happiness.

Hannah Glasse’s The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy was published in 1747. A fair proportion of the recipes in this book were copied from other books, as was common in the days before intellectual property law. However, Mrs Glasse managed to put her own spin on things, and moved things on by offering readers more clarity in her instructions on quantities, timings and visual clues.

For example, she wrote: “To roast a piece of beef about ten pounds will take an hour and a half, twenty pounds weight will take three hours,” and of “pig boiled till the eyes come out.” Admittedly, Glasse’s instruction for Black Pudding begins “First, before you kill your hog…” And the ‘receipts’ (as recipes were called then) for fending off the bite of a mad dog and the Plague are less useful now. There are, though, many recipes that sound appealing to contemporary cooks, such as Cowslip Pudding, a sort of floral baked custard flavoured with rosewater and cowslips.

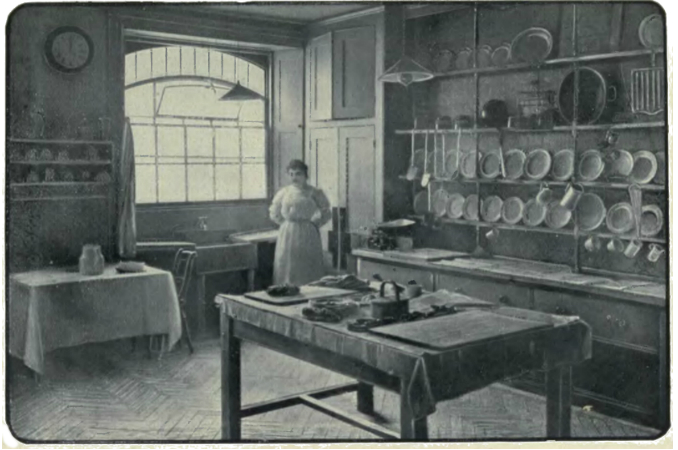

The typical kitchen of a grand house of the 19th century.

Good Things to Eat was published in 1911 by Rufus Estes, one of the first African-American chefs to write a cookbook. The book is introduced as a child of his brain, written in the little time he had after his day job cooking for Pullman private car travellers. It has several dishes that I want to cook and eat, Broiled Mackerel with Black Butter, Apple Sponge Pudding, Cocoa Rice Meringue, and Custard Soufflé among them.

From his recipes, it is apparent that Estes knew what people liked to eat and understood, as written in the introduction, “one of the pleasures in life to the normal man is good eating.”

Patience Gray's often-quoted Honey from a Weed is a ‘mere’ 34 years old. Charming and thoroughly enjoyable in tone, it is more than a cookery book – it is a manifesto for a simpler way of life and for striking a balance between “frugality and liberality.”

At times Gray sounds eerily prescient: “Once we lose touch with the spendthrift aspects of nature’s provisions epitomized in the raising of a crop, we are in danger of losing touch with life itself,” she wrote. I learned so much from this book, from geodetically cutting an onion in three directions (I had to look that up…), about immuring sprigs of basil in peach or quince jam, and that chickpeas gathered fresh are brilliant green with a taste of lemon.

The recipes range from those which have no bearing on my life, such as how to cook a fox and horse meat, to those close to my repertoire dishes: Pasta al Forno with minute meatballs and hard-boiled eggs, Red Bream Cooked in the Oven, and Spaghetti with Garlic and Butter.

Restoring meaning to cooking

Reading these books made me curious about the lives of the people who wrote them. Anne Willan’s Great Cooks and their Recipes as well as her other cookbooks were helpful in this regard.

I spent many happy hours going from one rabbit hole to another in researching this piece. The context of the lived experiences of the authors provided more nuance to their words. I agree with the words of Patience Gray, who wrote, “My ambition in drawing in the background of what is being cooked is to restore meaning.”

Tech tip for vintage cookbook junkies: when searching ckbk you can filter by era, and when viewing search results (or the main list of cookbooks) you can order the list by date publication, either newest or oldest first.