Behind the Cookbook: Classic Turkish Cooking

The Making of Classic Turkish Cooking

Classic Turkish Cooking was first published in 1995. Even though I had written many articles on food and different culinary cultures in the 1980s, and early 1990s this was my first book and it was one of the first books on Turkish food.

Over the years I have received many grateful letters and emails from Turkish cooks, including Ozlem Warren, the author of the award-winning Ozlem’s Turkish Table, to thank me for putting their cuisine on the culinary map and for giving them a collection of written recipes to work from.

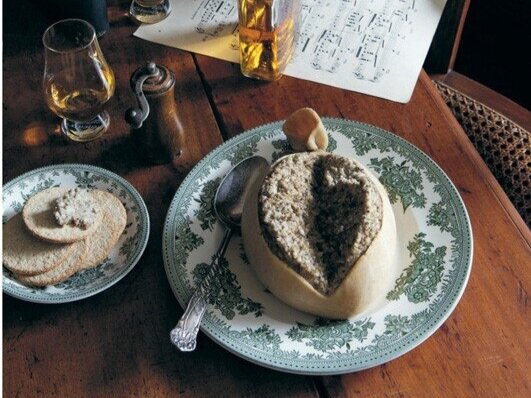

Unknown to many, though, the book was written and photographed in the depth of winter in the Scottish Highlands where my then-husband and I had bought a ruined croft to turn into a home. The mile-and-a-half track to the croft was snowbound, with drifts covering the fences and gates and the wind blew the snow into such high mounds that we could climb onto the cottage roof and slide down.

We didn’t have a phone so we had to walk to the nearest phone box to keep in touch with family, friends and work; we didn’t have any electricity so Tilley lamps and candles provided our main source of light at night; and we didn’t have a fridge so we used a bucket in the snow. We had a trickle of water from the outside tap and could fill up an indoor sink and we set up a small gas camp cooker for the coffee percolator and porridge pot.

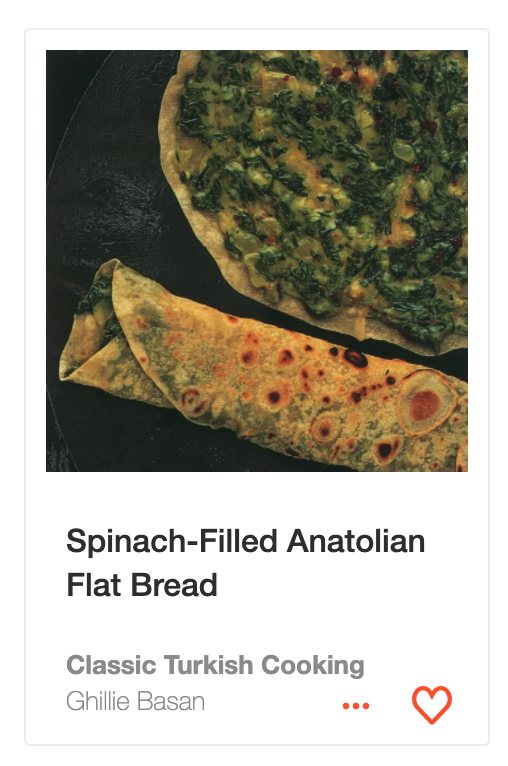

Lacking cupboards, we used an old whisky barrel for dried food storage and all pots, pans and utensils hung from hooks in the low ceiling. We made an outdoor grill with some old bricks and placed the kind of cheap metal grid you normally use for wiping muddy boots over the top – it was put to immediate use to smoke aubergines and make flatbreads. When spring arrived we foraged and prepared the vegetable garden and lived off wild rabbits and hares, or road kill if it was fresh. Crucially, we were happy in our primitive surroundings but we didn’t have any money.

So, one day, I blew the dust off a manuscript I had written a couple of years previously when we were living in New York. It was for a book on Turkish food, the first of its kind, but the Manhattan editors had rejected it as it was the era of the Iran-Contra affair and the Americans were jumpy about anything to do with Turkey and the Middle East so they asked if I could write the same book but call it Greek!

For a moment we had been gob-smacked. They seemed totally oblivious to the history of the region and the geopolitical ramifications of such a suggestion. This was in an era that you struggled to enter Turkey if you had a Greek stamp on your passport and vice-versa.

In history terms, the Turkish invasion of Cyprus was relatively recent and the resulting division of the island into Greek and Turkish territories was like a gaping wound. There were plenty of good books on Greek food in the US and UK market but it was hard to find anything on Turkish cuisine. We were on a mission to bring authentic Turkish food to a wider audience so we left the New York offices without a book deal but with our integrity intact.

Before tackling London publishers, I revamped the book and asked the well-known food writer Josceline Dimbleby if she would like to write the foreword to the book. She had a connection to an uncle on the Turkish side of my then-husband’s family who were descendants of the last Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire and lived in a large yalı built right on the Bosphorus. You could actually lean out the window of the dining room or salon and buy fish from a passing boat.

There were stories of soirées and dinners with royalty, diplomats, and famous writers and musicians and how the dirty china plates and silver cutlery would simply be thrown into the Bosphorus to clean! When Josceline had travelled in Turkey she had visited the yalı with her then-husband David Dimbleby, the BBC broadcaster, so she seemed delighted to write the foreword for us, and we hoped her name might spark a little interest among publishers.

When we did eventually gain a book deal it was with a publishing house that specialized in Middle Eastern texts of an academic nature rather than a culinary one and none of them had a clue who Josceline was, but we couldn’t afford to be choosy so we signed the contract at the beginning of winter and began photographing it in the snow.

The entire book was prepared and cooked using the bucket in the snow, the camp cooker and the makeshift outside grill. When it came to photographing the food, we placed a low table in front of the one window that the sun would light up in the afternoons and, as we didn’t have any electricity we relied on these bursts of sunlight, which I would reflect on to the dishes by standing outside the window with a mirror, to act as studio lights.

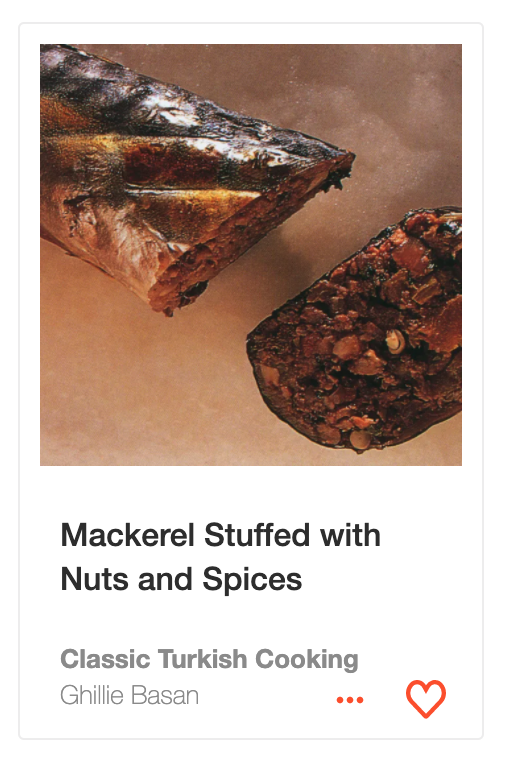

Whenever we opened the back door a draft would sweep dog hairs into the air and land them on the food and, on occasion, a small beetle or spider would crawl across the frame looking very like one of the coriander or nigella seeds on the move. A fresh mackerel that had to be massaged and squeezed to disgorge its flesh and bones while keeping its skin intact so that it could be re-stuffed presented a photographic challenge.

Once it was separated from the bones, the flesh was sautéed with onions, nuts and spices and then carefully fed back through the opening below the head so that it resembled a plump mackerel once more. This was the medieval Ottoman speciality, uskumru dolması, and freshly prepared it looked as magnificent as Sultan Süleyman would have liked but there was no sun that day so the mackerel had to go back into the bucket in the snow. It remained there for four days until the sun reappeared.

We snapped into action with plates and props and I danced outside in the cold with my mirror ready to catch the sun when it peeped out from behind the clouds but the fish had turned green and had begun to smell so we could only photograph a thin slice and had to bin the rest. Even our big Labrador dog, Biglie, who regarded sheep shit as fine dining, turned up his nose.

Twelve large wobbly bulls’ testes met with a similar fate. My mother had helped us procure them from her butcher who had wickedly announced “I’ve got twelve big testicles just for you” when the shop was full of bemused locals. Dressed in her tweed skirt and pearls, my mother turned crimson but laughed as she explained to the small gathering why she wanted them and then dashed them home, out of sight, to the depths of her freezer.

For a woman who enjoyed hosting lunch and dinner parties, she was remarkably generous with her freezer space. While listening to Woman’s Hour on Radio 4, she would cook for an army, filling her freezer with pastry cases, soups and stews, ice cream and sponges but, as the winter wore on and she began to wonder if we would ever make it over the snow-blocked hills to collect them, her patience wore thin. “When are you coming to get these damned balls?” she snapped down the phone, as we tried to suppress our laughter in the little red phone box at the end of the single-track road leading into our glen.

Once rescued and brought home, the defrosted testes languished in the bucket while we endured another non-sunny spell, so they too turned green like the mackerel and began to smell rancid. We sliced the best of the bad bunch and grilled them with finely chopped dried chilli and oregano, drizzled in melted ghee, just so we could photograph them. This time, Biglie was brave enough to have a nibble.

We were complete novices at food styling and photography so there was a great deal of trial and error and a lot of excess food to distribute to the farmer who lived closest to us. He was a real character with a spirit-pickled constitution and quite enjoyed the novelty of some of the dishes but he said they gave his bidie-in (local dialect for the person who lives with you) “the shits”.

Some days I would have to cook the same dish several times and whenever we ran out of an important ingredient there was no popping around the corner to the shop; it required a whole day to walk out, drive to the supermarket an hour away, and then walk back in again. Because of the time it took to shop and the lack of clockwork sunshine, our winter was consumed with the writing and photographing of the book.

I managed to get pregnant and have a baby in the time it took for the publishers to actually produce printed copies of Classic Turkish Cookery so the three of us set off for London to attend the launch. Held at the Turkish Embassy with an impressive guest-list which included Josceline, of course, as well as Claudia Roden and the Two Fat Ladies (Jennifer Paterson and Clarissa Dickson Wright), we felt like a couple of country bumpkins. I was worried about our six-month old baby, who was being looked after six floors up at the top of the building by a complete stranger but it wasn’t long before she was brought down to join us as she wouldn’t settle and had become hysterical.

It was the first time in her little life that she had been parted from me and she was a very sociable baby, so she was delighted to be passed around the launch guests who we didn’t even know. And, when overcome with exhaustion, she fell asleep on the ample bosom of the late Jennifer Paterson, who had arrived on her motorbike dressed from top to toe in shocking pink that matched her lipstick.

We were astounded when the book was shortlisted for the two prestigious UK awards at that time. We were up against well-known chefs and TV personalities who had teams of art directors, food stylists, recipe writers, and professional photographers compared to our pantomime of buckets in the snow and dancing outside with a mirror to catch the sun.

Suddenly, publicity trundled up the track to our door in the form of tabloid papers with cheesy one-liners like “Yabba dabba dough” as we were likened to the Flintstones and the three of us had to trek down to London once more. This time we chatted with Nigel Slater, Rick Stein, Antonio Carluccio and Philippa Davenport and a host of other celebrities who, as usual, we didn’t know as we didn’t have a television.

With good reason, we lost to Claudia Roden for her splendidly detailed masterpiece The Book of Jewish Food, which won just about every cookery award on the planet, but we gained a new book deal and headed home to the hills gasping for fresh air and the natural tunes of our active moor.

Ghillie Basan is a Scottish-based food and travel writer, cook and workshop host. Her books have been nominated for the Glenfiddich, Guild of Food Writers’, and Cordon Bleu awards. Her most recent cookbook is Spirit & Spice, also available on ckbk. For more about Ghillie Basan, including details of her residential cookery workshops, visit www.ghilliebasan.com or follow Ghillie on Instagram.

Ghillie Basan is a featured author on ckbk, home to the world's best cookbooks and recipes for all cooks and every appetite.

Ghillie’s kitchen in the Cairngorms today (much upgraded from the Classic Turkish Cooking days!)