Author Profile: Sumayya Usmani, author of Andaza

Andaza: A Memoir of Food, Flavour and Freedom in the Pakistani Kitchen (Murdoch Books) is published on April 13th 2023 and to mark the occasion, ckbk met with author Sumayya Usmani to talk about the book and its concept of “andaza”, essentially “the art of sensory cooking”.

To celebrate the launch, thanks to publishers Murdoch Books, ckbk has two copies of this brilliant book up for grabs for two lucky winners.

Scroll to the end of this article to find out how to enter and to check out Usmani’s recipe for Chicken Boti Tikka, Bundoo Khan Style. ckbk Premium Members have access to the full content of Andaza. The book is a hard-to-put down read exploring an early childhood at sea with a father who captained merchant ships, time in England, and then growing up in Karachi, Pakistan. Read on to find out how to be more “andaza” in your own cooking.

By Ramona Andrews

How did you put the book together with its stories and related recipes? Did you start with the stories or the recipes when writing it?

I began by writing just the stories that stood out for me and intertwined my relationship with food and the people who were involved in my childhood and coming of age – the recipes were merely within the text as conversations and lessons heard around the women in my family. There is that still in the book of course. I added actual recipes to the end of each chapter after my publisher suggested it would add a little extra to the book. I am glad I did. The book was all about “andaza” cooking, “the art of sensory cooking" whereby I picked up recipes and learned to cook in a visceral way. This is why written formal recipes are not the main focus of the memoir, but the narrative is.

Your mother articulated this idea of “andaza” beautifully in the title of the first chapter: "You can’t cook with words." What advice can you give to those of us who need the crutch of a recipe? How can we learn to cook in a more “andaza” way?

The best way to learn to cook is to trust your intuition with cooking and trust your senses too. This means you need to truly accept that cooking is a natural way of creating something that is nourishing and you know what makes you feel that comfort – trust it. If you approach cooking in this natural way, you suddenly don’t feel like a slave to a recipe. Slowly you begin to use the guidelines in a recipe as a story that you interpret in your own way and with that, you begin to trust yourself. Recipes become crutches because we let them. Sure it’s wonderful to be inspired by others' cooking and learn new ways of cooking, but ultimately it’s you or your loved ones who will be nourished by your food and it should, in many ways, be an expression of you.

Sumayya Usmani, author of Andaza: A Memoir of Food, Flavour and Freedom in the Pakistani Kitchen (Murdoch Books). Photo by James Melia.

What ingredients do you like to work with best and how can we be more “andaza” with these ingredients?

My advice to cook in a more andaza way is to use the freshest most seasonal ingredients and let them guide you. Sometimes we think we need to be overly complicated, but you don't have to be. I had to substitute so many ingredients when I moved to Britain. I could get certain imported ingredients in Asian shops but the andaza way is to use memory and sensory recollection to create flavor with techniques and flavor styles to inspire changes and alterations in recipes, and recreate recipes. So the challenge of not having all the ingredients actually facilitates andaza cooking.

The book is not conventionally structured with recipes ordered into starters, mains and desserts or grouped together by ingredient. There is the title inspired by your mother's words: "You can't cook with words" and also chapters entitled "The hope at hospitality's heart", "Chaat isn't a starter" and "Dadi's free spirit". What other food stories and writers have you loved that have inspired your own story-telling and the way you structured the book?

There is nothing conventional about the book or about me for that matter! Because this book was always going to be a memoir, the chapter titles and story structure was driven by this slice of my life – the childhood to coming-of-age story and how comfort around food offered security and belonging. I have been greatly influenced by many writers and books – this has both inspired my storytelling as well as compelled me to stay adamant about how I must tell my story as well. Though this book is food fiction, I have always loved Like Water For Chocolate by Laura Esquivel. It really inspired me to tap deeply into that body and mind connection with food and relationships and showed how feeding a family has a much deeper narrative than mere physical sustenance. A memoir I loved more recently is Crying in H Mart by Michelle Zauner and also, though not about food, A Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion – one of my favorites. I’ve always loved all the food memories by Ruth Reichl, especially Tender At The Bone.

The book is a real coming-of-age story, as well as a food memoir. Love stories, clandestine dates, illness, politics, family history. On reflection, what now are your most cherished food memories that you evoke in the book?

I would say the time of first love and how food played a part in those clandestine meetings, the time on the ship, and my relationship with my mother and Nani Mummy in the kitchen in Karachi would be my most cherished ones. As well as the time with my favorite aunt, Guddo, who we lost way too early.

What are your go-to comfort foods that remind you of a) life on the ship, b) the year you spent in England as a child and c) the rest of your childhood in Karachi?

Fox biscuit tins on the ship. Huge ones with layers and layers of different biscuits. So much so that we were so spoilt for choice, we’d eat one half popped back into the tin and try another! For my time in England, cola bottle jellies and sweets at the post office shop generally, especially popping candy. For Karachi, chicken tikka (quarter chicken on the bone barbecued with spices), kebabs in parathas called kebab rolls, chaat on the streets, and bun kebabs which are like a Pakistani burger!

In the book you describe how hospitality and sharing food with others, "isn’t just at the core of my mother’s personality but is also the basis of a cultural generosity that runs through her veins, as well as mine." We love this idea of cultural generosity and want to hear more about what hospitality means to you. What do you love to cook for other people?

You can’t go to a person's home in Pakistan for a casual meeting or have someone over without being fed or displaying a huge spread. Most people will serve guests what they can’t afford partly to show off ;) but mostly because it’s the concept that guests are kings in one’s home and to give them the best is our duty. Letting someone go without feeding them something, even a snack or two is just disrespectful and rude! For a casual chai evening - I love making dahi baras [fried lentils in yoghurt] or green chutney sandwiches that my mother always made for guests. They remind me of the ritual of chai time in Karachi.

What was the last thing you cooked from the book and why do you like to return to this recipe?

It would be Firni - ground rice pudding. I miss my Nani Mummy often and this is a recipe that reminds me of her so much. I learned to cook it from her and it offers comfort through the toughest times.

What was it that prompted your change of career from law to food writing? Tell us about how this came about.

I never had a passion for law as I was always a creative person, restless all my life. I couldn’t find what it was that was my true calling. When I began writing my blog in 2009 and after moving to Britain in 2007 I realized that food and writing was what set my soul alight. I’d always written for myself and it helped me make sense of my world. I suddenly found I really felt this would be a career path that might give me the creative life I so longed for. Working with Madhur Jaffrey on a TV show in 2011-12 was the push I needed to take up writing and food full-time as I realized I needed to do it to truly be happy.

Where would you call home now and what dishes remind you of it?

I don’t know where home is. Does anyone? No one place makes me feel like I’m connected to it. But food offers me a sense of belonging and always will. It doesn’t matter where I cook or what I cook, it doesn't even have to be childhood recipes. The act of nurturing myself with something I've cooked for myself is what creates home for me.

We were surprised to see recipes for beauty preparations in the book - there's a homemade eye kohl and a wedding "ubtan", a face and body scrub. What makes these homemade beauty products special and do you have any other beauty traditions?

Beauty and the kitchen go hand-in-hand in Pakistan. So many of our beauty products and make-up are made in the kitchen – I felt that it was important to include those which my mother holds sacred because they were such a big part of my life growing up in the kitchen, they also taught me what it meant to be a woman and nurture myself. There are many masks that are made in the kitchen such as yoghurt mixed with turmeric and lemon for brightening or red lentil scrub with rosewater. There are many beauty traditions in Pakistan too, like sugaring or waxing hair with kitchen-made body wax!

What are you working on at the moment and what are your plans for the future?

I'm working on a new non-fiction book proposal which is a braided story of history, memoir, folklore, and flavor. I am also returning to university this autumn to do my MLitt in Creative Writing, which I know will be the best decision of my life. This is the time for me I believe – I turned 50 this year and I'm so ready to be reborn as the writer I was meant to be.

Chicken Boti Tikka, Bundoo Khan Style from Andaza: A Memoir of Food, Flavour and Freedom in the Pakistani Kitchen by Sumayya Usmani (Murdoch Books, £25). Photography by Jodi Wilson.

Chicken Boti Tikka, Bundoo Khan Style

Family weekend trips to our favourite open-air barbecue restaurant meant we’d get to eat boti tikka with flatbreads and tamarind chutney – as the grown-up chat bored me, that was the only reason I’d willingly go along. For this recipe (pictured above), you’ll need some bamboo skewers to thread the cubes of chicken on; remember to soak them for at least half an hour so they don’t get singed in the oven. Serve with naan or basmati rice.

Prep time: 25 minutes + marinating time, from 1 hour to overnight

Cooking time: 25–30 minutes

Serves 4–6

Ingredients

½ teaspoon chilli powder

½ teaspoon crushed black peppercorns

¼ teaspoon turmeric powder

1 teaspoon cumin seeds, roasted in a dry frying pan and ground

1 teaspoon coriander seeds, roasted in a dry frying pan and ground

½ teaspoon garam masala

½ teaspoon unsmoked paprika

3 garlic cloves, crushed

2.5 cm (1 inch) ginger, finely grated

salt, to taste juice of 1 lemon

4 skinless chicken breast fillets, cut into 2 cm (¾ inch) cubes

2–3 tablespoons sunflower oil

For the tamarind chutney

100 g (3½ oz) dried tamarind – about half a block

4–5 tablespoons dark brown sugar

1 teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon cumin seeds, roasted in a dry frying pan

½ teaspoon crushed black peppercorns

½ teaspoon chilli powder

In a large bowl, mix the spices, garlic, ginger and salt with the lemon juice. Add the chicken and leave in the fridge to marinate for at least 1 hour, or as long as overnight.

In the meantime, soak about 6 bamboo skewers in water and make the chutney. Put the tamarind into a small saucepan with 150 ml (5 fl oz) of water, the sugar, salt and spices. Bring to the boil and stir until the block of tamarind breaks up and the sugar and salt have dissolved, about 10–15 minutes. Strain through a fine-mesh sieve into a bowl, discarding the tamarind seeds and cumin seeds. Set the chutney aside while you cook the chicken.

Preheat the oven to 180°C (350°F) and line a baking tray with baking paper. Thread about 4 chicken pieces onto each bamboo skewer, then place on the baking tray. Brush the chicken with oil and cook for 20–25 minutes in the oven, or until the chicken is brown around the edges and cooked through.

Serve hot, with the bowl of chutney alongside.

The chicken tikka was always spicy and made my tummy rumble the minute I saw it. I’d pull off pieces of the chicken meat, roll it up in hot naan and reach for the chutney.

ckbk Premium Members have access to the full content of Andaza: A Memoir of Food, Flavour and Freedom in the Pakistani Kitchen and more than 700 other cookbooks.

Win a free copy of Andaza

We have two copies of Andaza to give away. For your chance to win a copy of the book, simply email us at hello@ckbk.com with “Andaza draw” as the subject title and we will select two lucky winners from the entries at random. Please enter by 23.59 GMT by 28 April. Good luck!

Top recipes from Andaza

More features from ckbk

Consuming Passions: Chocolate

Joy Skipper reflects on her passion for chocolate and shares findings from visiting cacao plantations and chocolate makers

Author profile: Ashley Madden

A Q&A with the creator of the Rise, Shine, Cook blog and author of The Plant-Based Cookbook

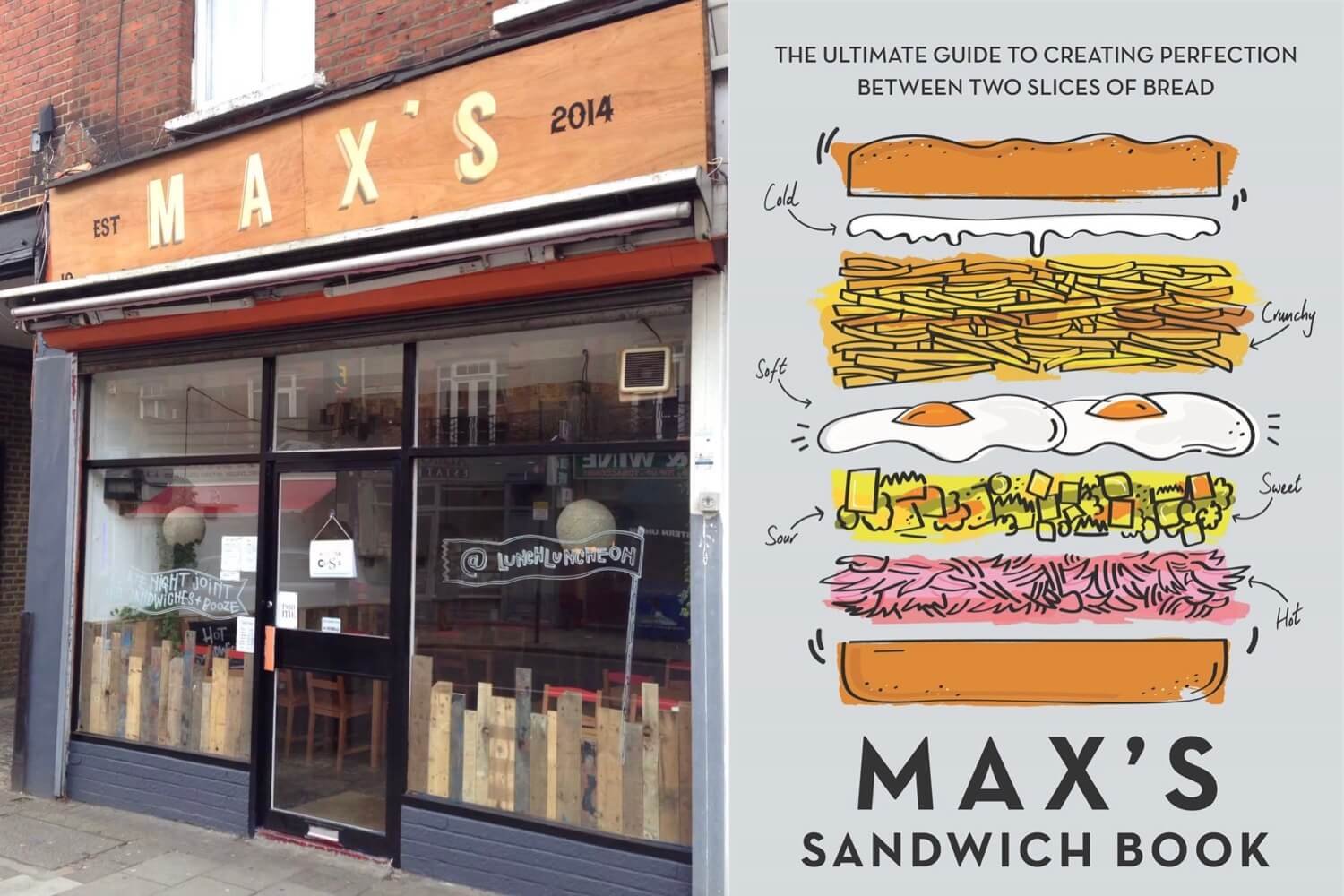

We speak to the founder of Max’s Sandwich Shop about his reinvention of the British sandwich